transforming plans to ships

In the first half of 1940 the ongoing war started to look more and more like a one sided affair with German victories following one after the other. The fall of France in June was the final trigger for a major USN fleet expansion program. Originally the General Board of the Navy wanted additional Iowas to make up numbers, but some opposition from Congress claimed that the 45.000 tonners were disappointing and it would make more sense to make up ground by building “markedly superior” battleships of 75.000 tons with twelve 16″ guns with corresponding protection and a maximum speed of 35 knots. The US was thought to be massively falling behind in the number of modern battleships, despite the 10 hulls already on order: based on Naval Intelligence data an estimated total of 34 battleships would be in the hands of the three major Axis navies when they complete their ongoing building programs. With the fall of France the threat from the Atlantic side seemed to be more real than ever, in addition to the reportedly massive Japanese re-armament. Therefore Congress voted the ‘Two-Ocean Navy Act’ on 19 July 1940 that authorized a 70% addition in tonnage, that translated to 1.325.000t total out of which 385.000 was allocated to battleships alone. The huge amount of ships ordered in the Navy act also meant that existing designs would be mass-produced instead of delaying construction waiting for a better design. What’s more the Navy (the General Board and the CNO) got a free hand on what it wanted to build, there was no need for political approval other than the Secretary of the Navy’s one. Only the President had overall control above them. Ultimately he disapproved the initial plan to build seven BB-61 repeat hulls and indstead only approved two with the rest of the tonnage going to five much larger ships, now designated BB-67 class and then calculated to be 59.000 tons standard, hence the total amount of 385.000 tons. Therefore the Montana class became an exception to mass production policy and this made the finalization of their design ever more urgent.

| Hull No. | Name | Class | Builder | standard displ. (t) | Planned completion date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB-65 | USS Illinois | Iowa | Philadelphia NY | 45.000 | |

| BB-66 | USS Kentucky | Iowa | Norfolk NY | 45.000 | |

| BB-67 | USS Montana | Montana | Philadelphia NY | 59.000 | 1 Sep. 1945 |

| BB-68 | USS Ohio | Montana | Philadelphia NY | 59.000 | 31 Dec. 1945 |

| BB-69 | USS Maine | Montana | New York NY | 59.000 | 1 July 1945 |

| BB-70 | USS New Hampshire | Montana | New York NY | 59.000 | 1 Nov. 1945 |

| BB-71 | USS Louisiana | Montana | Norfolk NY | 59.000 | 1 Nov. 1945 |

| Total: | 385.000 |

Final designs (September 1940-January 1941):

The General Board made it’s decision for the BB-65A which had the 212.000 SHP powerplant of the Iowa class and was fully protected against the heavy shell from 18-32.000 yards. Clearly this one seemed to be the best compromise between speed, protection and firepower from the miriad of preliminary designs and was just manageable in size for all Navy Yards. Also this design already featured a secondary, lower, inner armor belt as a protection against diving shells – it was a continuous strip of heavy armor placed on the innermost, main torpedo bulkhead.

A month after the passing of the Two Ocean Navy Act the General Board met again and agreed on the characteristics of the new battleships, taking into account the wartime experience from the European front and also the now prevalent political situation and all it’s implications (fast battleships priorized, no limit on BB construction, no beam limitation, new ships must be at least 25% more powerful compared to adversaries). The characteristics based on preliminary data called for a displacement of roughly 58.000 tons standard. From here onwards the class and plan’s designation changed to BB-67 from BB-65 in accordance with the now ordered hulls. Also the following sub variant numbers indicated a stage of the final design work instead of marking separate concepts or variants.

BB67-1 from Sept 1940 was the first detailed design, based on the preferred BB65-5A variant of the previous series. It relaxed the length requirements a bit to 890′ (from 880) in order to comply with characteristics laid out by the General Board earlier. As we saw previously War Plans favoured length reduction as much as possible in order to handle these ships in as many ports as possible (esp. in damaged condition) and have the best tactical manuverability.

Unfortunately displacement jumped to 61.000 tons (from 58.500 in BB65-5A) as more detailed weight calculations were done and experience gained from BB-61 class ships construction started to trickle in. By this time AA armament was figured into the calculations with the addition of six 1.1″ quad mounts and 12 single 0.5″ machine guns. Main battery ammuniton was set at 75 rounds per gun while secondary battery guns had to make it with only 340 rpg.

In the meantime BuOrd improved the design of it’s Mark 7 16″/50 gun which was intended to equip the class. Muzzle velocity now increased to 2500 feet/sec meaning more penetrative power on the inner edges of the immune zone.

BB67-2 of Oct 1940 answered this by thickening the main belt from 15.75″ to 16.1″ to maintain the IZ. Main transverse armored bulkheads were 20.3″ both fore and aft. At the same time the deck thickness could be relaxed somewhat to 5.8″ from 6.2″ thanks to the flatter trajectory due to the higher muzzle speeds. To refine the armor depending on the spot it protected the main armored deck’s edges were thinned back to 6.1″ only and a 60 pound STS plating was added to the entire side above the main armored belt (sort of a secondary or upper belt). This change cost only 200 tons in direct displacement, but total displacement rose almost to 61.400 tons! In that there were some further weight additions, like ammuniton allowance increasing to 100 rpg for the main guns and 500 rpg for secondaries.

Some measures were needed to curtail further weight growth as for little added capability displacement was already 5% overweight. Even without treaty limitations this was not desireable.

BB67-3 from Nov 1940-Jan 1941 introdcued some weight saving measures as a result and also brought about one of the most controversial and highly debated changes to the design. The idea was to take out the 13.5″ thick after belt and relevant deck armor portion (present on the BB-57 and BB-61 class too) that covered the connections of the steering gear armor boxes to the main citadel. It was suggested to use 6″ thick armored tubes instead that covered only the wiring leads. This way standard displacement could be kept at 59.700 tons.

The General Board hearing on 22 January 1941 covered the topic in detail and questioned BuShips on the change. Lt. Commander Kniskern from BuShips made a very detailed argument on the change:

He argued that the existing aft belt was set well inboard from the side plating and reached up only to the waterline contributing little to reserve buoyancy protection. Moreover the deck covering it only extended the part between the upper edges of the aft belts so it protected only the inner shafts from bomb damage anyway. They tried to have one flat deck only that was lower in the ship to cover all the shafts and stearing gear leads but it weighed as much as the previous box solution and offered no protection of reserve buoyancy either as there was no bomb deck above it. Finally they came up with the armoured tubes solution as it was much lighter and offered further advantages:

- weight saving as the the whole main armor box could be moved aft

- much finer hull lines aft as less bouyancy was needed to support he hull aft

- the reduced fullness of the body aft also meant reduced power requirements for the propulsion

He further added that in fact BuShips is not too concerned about the propellor shafts as those are made out of 28″ diameter “special alloys steels with a factor of safety of about eight against normal operating stress” – so essentially he considered that no protection is needed for these. On the topic of reserve bouyoancy /hull volume protection aft he commented that the flooding characteristics of the hull are such that it would tolerate the complete flooding of the part between the main and steering armor boxes and still remain operational, though with a trim aft. Underwater damage would cause the same flooding there and no protection was offered against that by the extended aft belt/deck either.

He recognized that 6″ thick tube walls might not tolerate a direct impact by a 16″ shell, but there were two tubes, redundant, pretty deep in the ship, both running in different locations, one higher up, one low (refer to the drawing). Chances were very slim that both would get severed by the same hit. In the end the tubes were 1 feet inner diameter with 7″ top and 3″ bottom walls.

This solution would save 600 tons in direct weight aft, would allow to move to a smaller, 172.000 SHP plant and would leave more space forward for the magazines of turret No.1.

Doubling the thickness of the armored tubes would add back 500 tons, so would almost negate the saving, while an other option, defining an IZ of 20-30kyards only for the aft armor box might allow similar weight saving.

BB-57, a short hull ship, had a secondary armor belt aft of the the after transverse armoured bulkhead and it trunked into the stearing gear’s armored compartment. This whole area aft was covered with deck armor as well, thereofe it essentially extended the citadel aft to encompass all steering related items. In fact both deck and belt here was thicker than the main parts. BB-61 class was very similar but with the trapezoid part being more elongated to cover the greater lenght.

However on BB-67 two turrets aft meant there had to be a lot more hull aft to support the additional weight (actually more than twice the weight due to one turret/barbette being in superfiring position). The much larger hull volume aft needed much more armor to cover the steering gear leads and the shafts, leading to even more weight aft that pushed the center of gravity aft therefore needing even more hull volume to support it and so on. The easy way out was to separate main and steering gear armor boxes and switch to direct armoring of steering gear leads and leave the deck and side unarmored between the boxes. This enabled pushing forward the CoG and much reduction in hull volume aft, also reducing probable flooding.

It was pretty clear that the 4th turret aft upset the weight balance of this length limited hull and any weight that could be taken out aft would greatly improve the balance of the whole ship.

Therefore additional weight saving came from shaving of some armor thicknesses from the gun turrets and main armored bulkheads. The latter were reduced from a maximum of 20.3″ both fore and aft to 18″ tapering to 15″ forward and to 15″ tapering to 12″ aft down to the top of the triple bottom, where 80# STS plating was inserted down to the outer skin.

Also the underwater protection against diving shells was finalized around this time on BB67-3 with a 7.74″ inner belt added onto the 30 pounds (0.75″) thick torpedo bulkhead. Later this was redistributed to 8.4″ tapering to 1.5″ over magazines and 7.1″ tapering to 1″ over machinery spaces.

Hull model tank towing tests and calculations also revealed that with the existing 212.000 SHP Iowa class plant 29 knots is achievable, but 170-172.000 SHP would be enough for 28 knots. This point was also debated for quite some time but a conclusive decision was not made until January 1941 to go with the smaller plant. It was again in conjuction of additional weight savings aft.

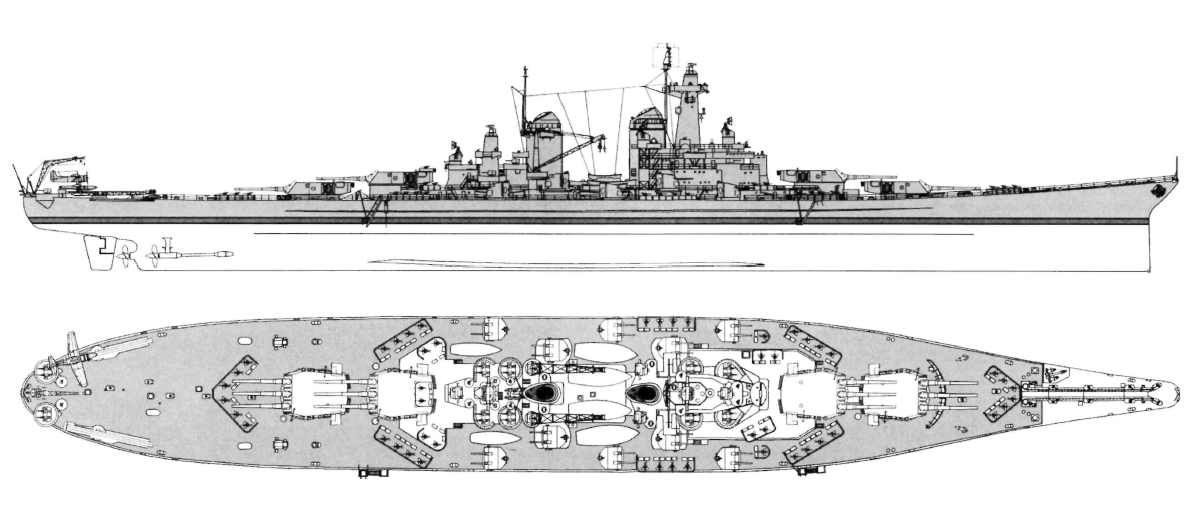

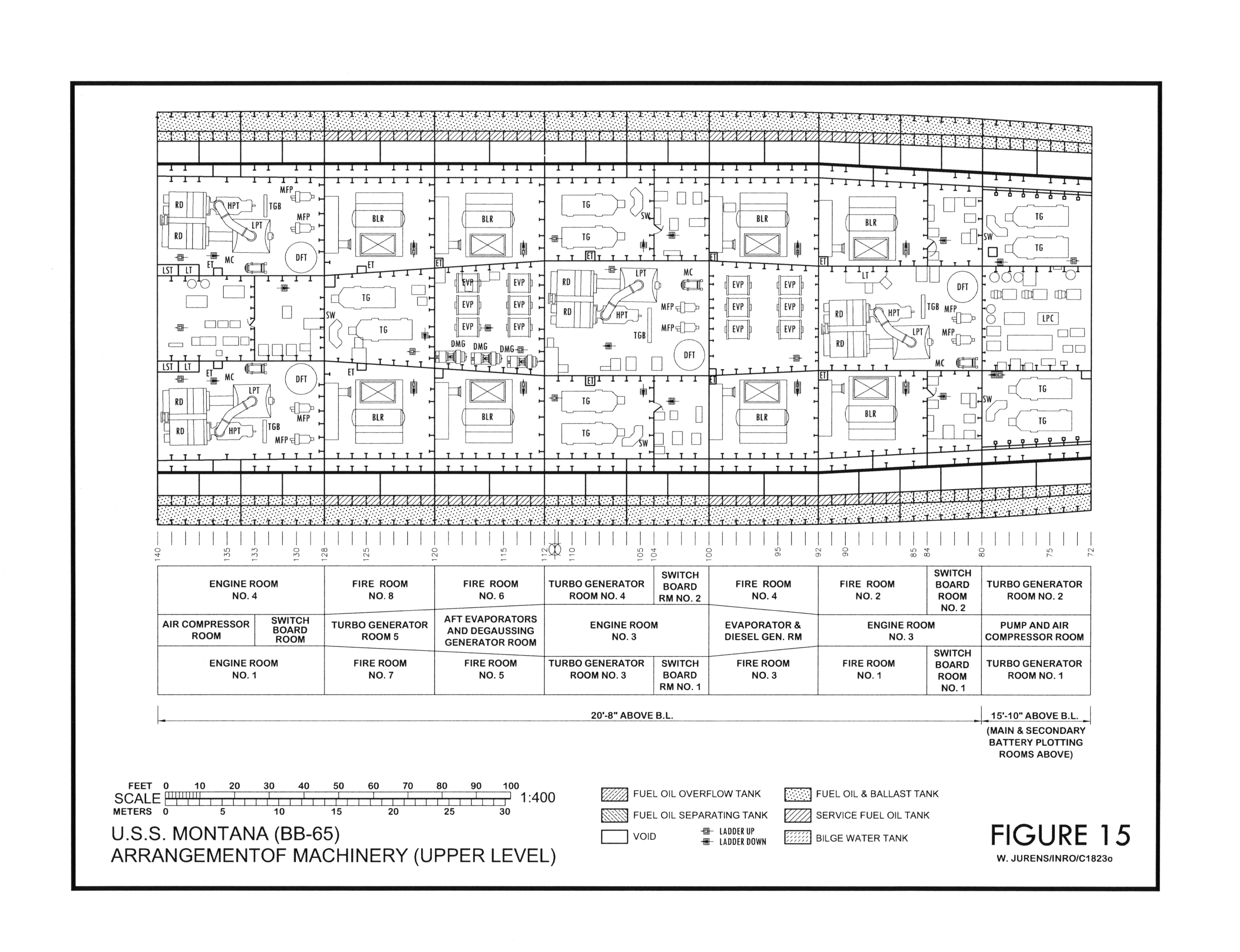

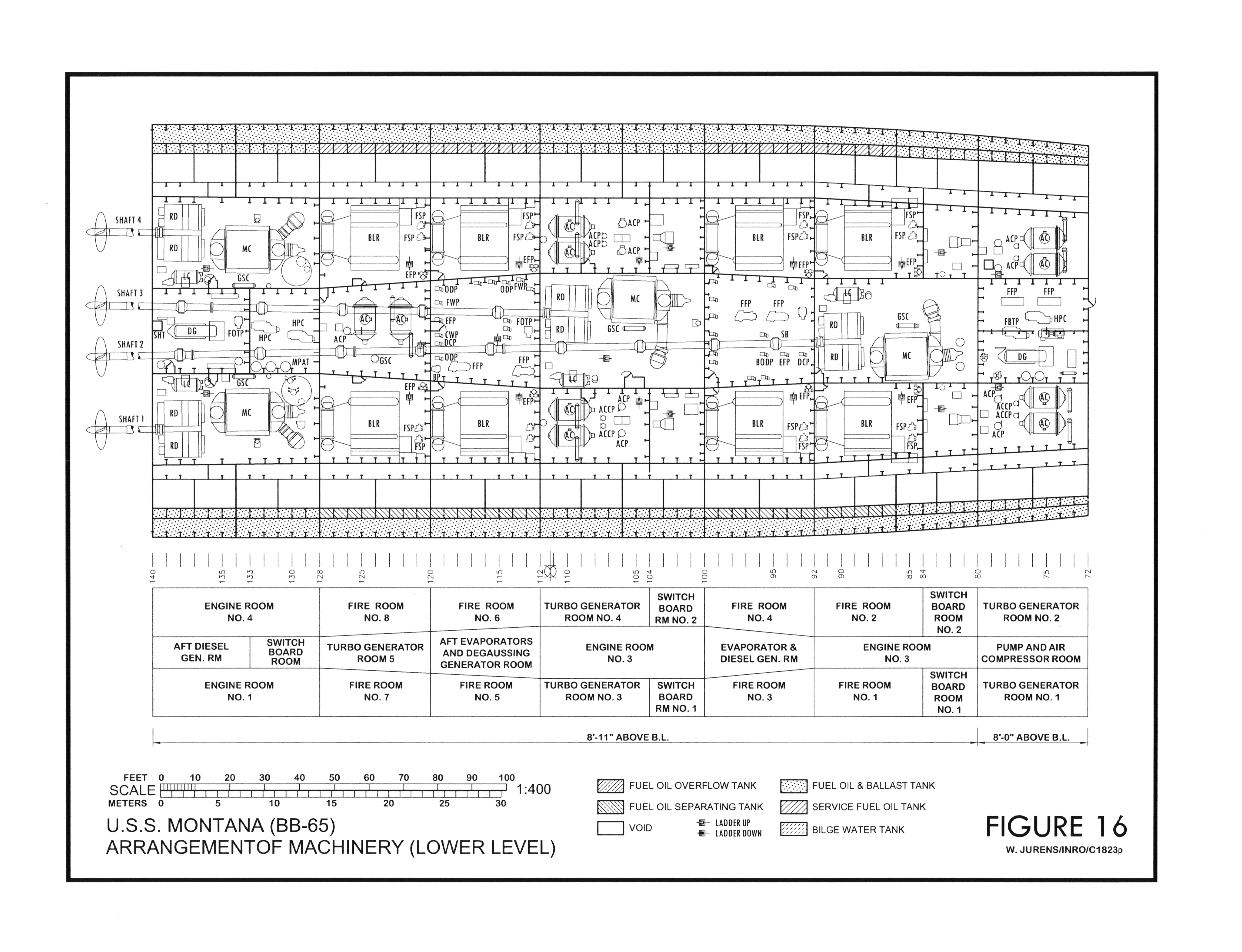

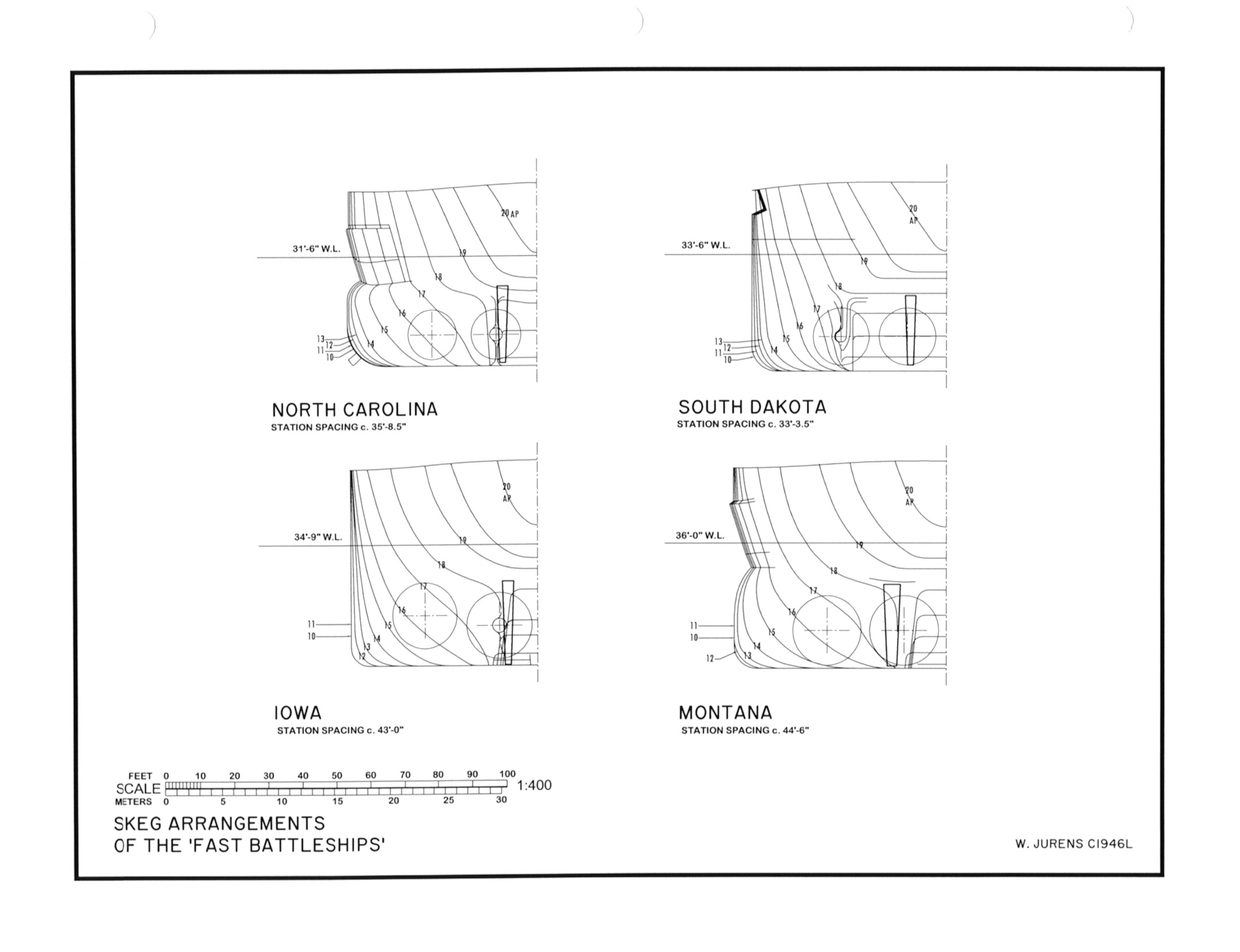

First of all the machinery spaces received a complete redesign from what was employed so far on the two preceeding fast battleship classes (BB-57, BB-61). The so far utilized unit machinery (where each compartment housed two boilers, a set of turbines and a set of aux. machinery) gave way to a finitely subdivided, complex system of small compartments – just compare the below drawings with the previous Parts’ similar ones for the other classes. The arrangement somewhat resembled the Lexington class battlecruisers’ turbo electric plant layout, except that in this case the boilers fed geared turbines instead of electric generators. The two turbines driving the inner shafts were located in the middle, each shielded by two boilers and a turbo generator room, each in their own separate compartment, on both sides. The two sets of turbines driving the outer shafts were placed behind the boiler rooms on each outside row of compartments (refer to the drawing below). This arrangement also precluded the need to run shafts under boilers so they could fit beetween triple bottom and third deck, like in the BB-55 class’ arrangement. Boilers would be single uptake type and somewhat smaller than the ones used in the BB-61 class. (Babcock & Wilcox would be the main supplier of these, with possibly two of the eight coming from Foster Wheeler in the two New York built ships.)

This way subdivision jumped enormously from 8 large main compartments in BB-61, that were running the full width of the citadel, to 26 small ones that were only one third of the maximum width. It would take 8 very precisely spaced torpedo hits (4 on each side) to achieve a mission kill.

Previously longitudinal bulkheads in machinery spaces were discarded as it risked assymetrical flooding that could lead to capsizing of the ship. However here the designers had a much wider beam to play with and a division into three parts instead of only two mitigated this risk to an acceptable level, especially if skirted by a much deeper and stronger TDS. However it is indicative of why War Plans and some other members of the design team were so concerned with draft in damaged conditions: with their huge beams these ships could easily dip into the 40’+ draft zone.

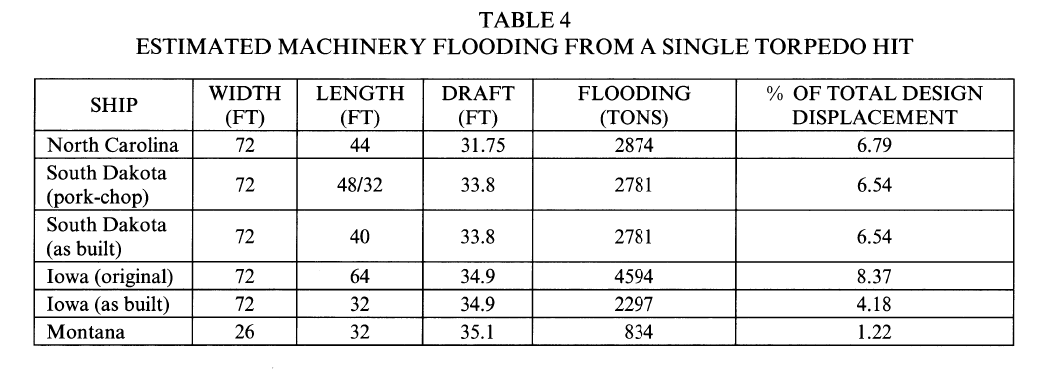

Calculations showed a four fold improvement compared to BB-61 in torpedo resistence from a single hit, based on calculated flooding:

This new machinery arrangement saved space, so hull length between the two inner barbettes (no. 2 and 3.) was not depending on machinery space length anymore, rather on buoyancy and deck space requirements (to fit in the secondary battery and superstructures). While the miriad of additional bulkheads added in about 200 tons of direct weight it was more than compensated for by reduction in armored length of the main machinery (saving 250 tons) and less powerful machinery (600 tons). To mitigate the concerns surrounding the armored steering gear lead tubes the bomb deck was extended aft too, at the cost of 230 tons added back.

The major takeaway here was that protection aft and associated heavy weights directly influenced the machinery size and layout and the two issues can not be separated. That is why reduction of thickness of the aft transverse armored bulkhead closing of the main armored box was strongly suggestes and done (see above) together with the lengthening of the hull forward to reduce resistance and to gain speed with the smaller machinery (see below).

The other part of the ’41 January hearings dealt with the secondary and anti-aircraft batteries as the air threat became ever more obvious. The 1.1″ guns were replaced by quad 40mm Boforses, for a total of six mounts, while the 0.5″ machine guns were changed to 20mm Oerlikons on a one by one basis. This again added 20 tons in direct weight and some more in ammunition. It was contemplated to change the secondary battery to the old venerable 5″/38 guns to save some weight but it was discarded as the 5″/54 was held superior in every aspect.

Now with all these changes displacement was curtailed back to 59.700 tons – ironically it was unanimously agreed to allow the ship to grow somewhat and so length requirements were relaxed to 910 feet (even 950 was discussed) while displacement could go as high as 61.000 tons. Neither were taken up for BB67-3.

By this point in early 1941 the design was close to reaching it’s final form with more detailed design work starting in paralel. Preliminary Design passed work to the Detail Design Branch in late March 1941. Some important questions, like selection of hull lines still remained open.Hull design and contract plans were to be done by the New York Navy Yard while gun turret plans were to be worked out by Philadelphia Navy Yard, just as in the case of the Iowa class.

BB67-4 was the last and final preliminary design, essentially the ship as selected for production. The only major change was the increase of armored freeboard from 8 to 9 feet. The superstructure underwent some rearrangement as well to facilitate the best possible firing arcs for the 40mm battery. The number of mounts increased to 8 quad mounts, two high up on each corner of the superstructure. Somewhat later an additional pair was added at the stern, on both sides of the aircraft handling crane.

Main gun ammunition was fixed at 100 rounds per gun with 360 rounds mobilization reserve, for a total capacity of 1560 rounds. Secondary battery ammo was set at 10.800 rounds (out of which 4000 was mobilization supply), so it meant 680 rpg in normal loadout.

Total standard displacement rose to 60.500 tons.

Mid-March saw the finalisation of preliminary design with the Contract Design Branch taking over design responsibilties entirely. Contract design however dragged on a lot as most of the existing contract plans were released in April 1942 and even as late as July 1942 some more were added. This long period was presumably due to the huge workload on Contract Design Branch and due to the immense size of the ship requiring several tens of thousands of drawings.

YaRDS, Docks, Planned construction start and finishing dates, individual weight details, flagship version

A major change regarding construction of these ships came early on: in February 1941 the decision was made to build all these new ships in building docks instead on slipways like the previous hulls. Beam was especially an issue at New York Navy Yard besides expected launch weights were really at the upper end of what can be handled from a slipway. The planned new, 1092 by 143 feet drydocks in the three major East Coast navy yards (two already under construction by that time) were the obvious choice, being able to handle the humungous hulls of the new battleship class. The Navy Yards had the new building docks under constrution exactly in order to support any new, larger battleships (see part 1.) while the yards themselves had the most experience in battleship construction. The private yards involved in the construction of the BB-57 South Dakota class were all busy with aircraft-carrier and cruiser programs. Although there is no firm evidence but the pending order of five hulls probably influenced the decision to order five docks in total.

New York Navy Yard was selected again as the lead yard despite being assigned hull numbers BB-69 and 70. Just as in the case of the Iowas part of the detail design process (hull design) was outsourced to them as they had the only viable size moulding loft for such huge ships – hence the lead yard.

Originally it was planned to use Slipways No. 1 and No. 2 at the NYNY to construct BB-69 and 70 but this was overruled in Sept 1940 for several reasons. The slipways were not wide enough to take on the planned 120’+ beam of the new hulls without reconfiguration. The overhead gantry crane system had to be taken down and completely rebuilt in order to allow for the widening of the slipways. These however were still to be occupied by the hulls of BB-61 Iowa and BB-63 Missouri for quite some time and the earliest date they could take on any new keels after reconfiguration was estimated to be Jan 1944. (Scheduled completion dates at this time were set as 1st July and 1st Nov 1945 for BB-69 and 70 respectively.)

Navy yard representatives argued that a large building dock would be needed for any major new construction as the largest exisiting dock couldn’t even take on an 45.000 ton Iowa class hull (final fit out of both BB-61 and BB-63 had to be done in the Bayonne Naval Annex Drydock). Thanks to the funding by Congress this was granted and an additional dock was provided for in order to build the two planned hulls in paralel. Works started in April 1941 on the two building docks No 5. and No 6. Completion was expected in December 1942 (actual completion was Feb. 1943), somewhat later then the ones at Philadelphia. The somewhat shorter space available for the entrance to dock No. 5 is mentioned by some sources as the reason why the final design phase shaved off 30 feet from the lenght (from BB-65-5 to BB-65-5A).

USS Maine BB-69 would have been the first to be laid down at New York, most probably in Building Dock No. 5, and as such the lead ship of the class in terms of planned construction times. She was therefore ordered as a fleet flagship, continuing the trend established by the first ships of the South Dakota and Iowa classes. This basically meant that an extra level was added to the armored conning tower’s base, in addition to the captain’s bridge and fire control levels there was a third, admiral’s bridge. Based on experience from the former two fleet flagships the top of turret No. 2 would have been left empy of any raised gun mounts in order to clear the vision slits and bridge windows for the lowest level of the bridge.

June 1942 weight data for BB-67-4’s Force Flagship configuration shows 57.534 tons light, 68.317 tons trial and 70.965 tons full load disaplcement with a calculated maximum of 71.922 tons. With this she would have been the largest battleship not just by sheer size but by weight as well.

USS New Hampshire BB-70 would have followed soon after her sister, as Building Dock No. 6 was completed very shortly after No. 5. With that New York Navy Yard would be building two of the world’s biggest battleships almost completely paralel (the Iowa class ships having been started with about a 12 month gap in their keel laying dates).

BB-70 would have represented the Division Flagship configuration of design BB-67-4 and May 1942 calculations showed 57.414 tons light, 68.135 tons trial and 70.783 tons full load displacement with 71.762 tons maximum listed. Most of the ~200 tons weight difference was made up by the extra level of the armored conning tower. With the lighter superstructure there would have been extra topweight available later on for added radar masts or more AA (especially atop turret No. 2).

Philedalephia Navy Yard was the other major player in the fast battleship construction program and in some respect much better suited to take on the huge new hulls. While the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn was relatievely boxed in by the surrounding metropolis and had cramped waterway run-ins to it’s drydock sills there was no such issue at Philadelphia. The wide Delaware river offered plenty of space to handle even the largest hulls. They also had two major slipways, suitable for battleship construction, however just as with NYNY, they were occupied by the hulls of USS New Jersey BB-62 and USS Wisconsin BB-64 until Dec. 1942 and Dec. 1943 respectively, meaning no new keels could be laid until then. What’s more Philadelphia had USS Illinois BB-65 assigned as well and she had to be fitted in paralel with the Montanas, making it building 3 of the world’s largest battleships almost in paralel, not an easy task (and probably a record if done).

When the decision was made to build all five ships of the class in building docks, Philadelphia already had it’s Dock No. 4 under construction, work starting in June 1940. Planned completion date was June 1942, with an estimated keel laying availability around Sept. 1941 and emergency docking capability by May 1942. (Probably this fact was influental in that numerically the first two hulls were assigned to PHNY in Aug 1940 after the Two Ocean Navy act authorization. Nobody knew then that detail design won’t be completed in time to allow the first hull to be laid.)

Dock No. 4 was a bit shallower than the two new ones at New York, with a maximum water depth to floor at mean high of 40 feet and maximum water depth to keel blocks at 35 feet compared to 43 and 38 feet respectively. Mean tide range was also much wider (5.6′ vs 4.2′) at Philadelphia so actual docking windows were more limited for deep hulls. This meant that a BB-67-4 hull could only be docked in light and undamaged condition and only at high tide. In May 1941 however a second dock, No. 5’s construction was started with a 43 feet 6 inches maximum waterdepth over the floor (38’6″ over blocks). This would have allowed docking a Montana class battleship for repairs in damaged condition or with higher loads as well. Since the docks were mainly meant for construction work this was not a primary concern but still important as large Navy owned docks were in relatively short supply on the East Coast. Planned completion was March 1943 for Dock No. 5.

USS Montana BB-67 would probably have been laid down in Dock No. 4 around the beginning of 1943. Although the building dock was already completed by the summer of 1942 the time needed for detail design by NYNY and armor/gun production would have prevented a much earlier start than the lead yard could do on USS Maine BB-69. Especially the lack of contract plans that the actual building process was based on made this impossible. She would have been built to the Division Flagship configuration, with an original (estimated in Feb 1941) planned completion date of 1st Sept 1945, a few month later than her NY built sister.

USS Ohio BB-68 would probably last to be laid down and last to complete as it’s intended building Dock No. 5 was scheduled to be ready by March 1943. Even with that if armor and gun production panning out as historical there was a good chance she could have been completed only a few month after it’s planned completion date in her division flagship configuration.

Norfolk Navy Yard was the third constructor involved with the class, taking on hull no. BB-71. In addition USS Kentucky BB-66 was assigned to the yard at the same time. BB-66 was laid down on the building ways formerly occupied by BB-60. It was intended that BB-71 would follow. However with the delay in Kentucky‘s laying down (up until March 1942) and Norfolk’s new Dry Dock No. 8. nearing completion (actually ready to take on a keel by March 1942) now the larger hull shifted there. Just as in the case of the Philadelphia built units, delay in detail design and working drawings prevented any work earlier.

1942 Armor chaNges

The first set of contract designs were completed in August 1941 by New York Navy Yard. It was soon circulated among commanders afloat and ashore, including quite a few people involved in the preliminary design stages. As could be expected the design drew a lot of critics. Admiral King, who was then C-IN-C-Atlantic Fleet was again critical of the excessive size and wanted a ship closer to BB-61 class dimensions but with the improved protection carried over. Admiral Kimmel, C-IN-C Pacific Fleet welcomed the improved subdivision and torpedo protection but based on his Battlefleet commander’s feedback questioned the limited number of secondary battery guns (it did not increase compared to previous classes).

The irony of the story is that even the Bureau of Ships was not completely happy with the design as indicated in it’s letter of May 1942 that was sent to the General Board (a few days after the suspension of construction). They argued that the class was designed with “gun actions against possible future battleships” in mind. However in the 13 month since the preliminary design was finalized circumstances have changed drastically and this called the above design principle in question. It was far more likely for a battleship to encounter enemy dive or torpedo bombers while at the same time the confirmed number of comparable enemy battleships with 16″ (or bigger) guns did not increase in this period. Furthermore new, more advanced radar fire control equipment becoming available around that time made the likelyhood of close quarter gun action fading fast (edit – history proved the contrary though in just 6 month time).

To answer the new, more likely threat vectors, BuShips suggested new armor alternatives, with belt armor reduced to BB-61 levels in Case A and to a middle ground value in Case B while deck armor increased to a composite total of 10.35″ for A and 10″ for B (up from the current 9.25″). Case B offered an inner IZ of 24k -33,5 kiloyards vs the 2700# shell. At the same time a converted 14″ AP shell dropped as a bomb would have to be released from 17.500 feet for a guaranteed penetration. The General Board agreed but did not answer the letter due to the suspension of construction on May 19 – therefore BuShips completed the contract design to the already approved BB-67-4 specifications on 4th August 1942. (Working drawings and mold lines would have taken at least until 1944 to finish and these would have been essential for construction to proceed.)

political wrangling, Suspension, building programs, cancellation

“This class of large battleships (ie the Montana class) embody a high degree of strength and a power of survival through their size, beacuase they are the only battleships which we have ever projected which were not artifically limited for othen than strictly military considerations. — Of all battleships built or projected for our Navy these represent the greatest power of survival and the most conclusive striking power, even if they never succeed in coming within range of any enemy battleship. In a military sense these ships should carry the most crushing and conclusive force in existence;” -wrote General Board member Rear Admiral Rawcliff who was the leading advocate for the class during mid-1942. In a similar toned letter the General Board indeed reflected back to the Secretary of the Navy (Frank Knox) in June 1942 with new, draft characteristics for the class. The General Board accepted the Bureau of Ships’ above mentioned suggestions for changing the priorities for protection. However all this was too late.

As it is clearly visible from Admiral Rawcliff’s enthusiastic and somewhat desperate letter above the Montana class was in a way crushed by it’s own superior strength and power. Bad timing, lack of industrial resources and a changing intra-Navy political setting and a lack of comparable opponent battleships all contributed to the unglorious end of these ships. (The size and guns of the Yamato class was not known to the US Navy until 1946.)

Before the war the General Board wisely front loaded it’s building plans with the battleships: they were coming first due to them taking the longest to build by far. As we saw in Part 1 external factors like lack of armor manufacturing capacity and other industrial shortcomings slowed things down even further. The Montanas were mainly the markedly pro-battleship General Board’s pet project, as they really wanted something unrestricted and extremely powerful. Yet there were a lot of intra-Navy opponents to this plan as we saw in Part 2, one of them being Admiral King (who was also a member of the General Board for a brief period, July ’39-Sept 1940). King did not oppose battleships in general, to the contrary, he was one of the leading advocates for keeping the type as late as 1944, besides he was the “godfather” of the Alaska class large cruisers. But he was not a true “Gun Club” member and during his career held carrier and aviation related commands mainly. What he disliked was the large size assoicated with the BB-65-5 and later the finalized BB-67-4 preliminary designs to the point that he sort of became a personal enemy of the class. He thought that such huge ships are impractical and do not offer military value in proportion to their size.

Added to this internal wrangling the value of the gun armed capital ship came into question by historic events. Hot on the heels of Pearl Harbor came the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse, greatly tarnishing the reputation of the battleship. The General Board defended the type arguing that the ships were subject to extremely powerful , concentrated attacks as they represented the strongest units of the fleet. Also the sunk prototypes in question were artifically limited and had innefective anti-air armament and also completely lacked air cover by fighter aircraft.

The President and the Joint Chief of Staff Board together with the General Board wanted to revitalize the ongoing capital ship program right after Pearl. Roosevelt directed on 10th December that all four BB-57 class ships under construction should “be advanced as much as humanly possible”. The first pair of Iowas, BB-61 and 62 ranked 3rd on the priority list, just after some Essex class vessels.

However things were about to change soon as the Chief of Naval Operations office was occupied by no other than Admiral King on 26th March 1942. The General Board’s relevance and it’s opinion’s importance sharply declined in the wake of Pearl Harbor and the combat experience derived from the ongoing war simply superseded it. Now things were dictated by the CNO’s office.

By April 1942 things did not look too rosy as there was an ongoing construction steel shortage plus the armor manufacturing capacity was still lagging behind needs. (Each Montana class ship would have required in total ~25.000 tons of various armor which was approx. 2 month worth of total production then. An additional issue was the individual size and thickness of plates, especially for the barbettes and turrets that were pushing the limit of existing manufacturing equipment.)

May 1st saw the President declaring that priority only to be given to ships that would be completed before 1st July 1943 (start of FY44). This effectively suspended the last four Iowa class, all five Montanas and all six Alaska class large cruisers, practically the better part of the capital ship program (eight Essex class carriers would be postponed as well). Adm. King succesfully protested, arguing that with likely potential losses the cut back program won’t allow an offensive in 1943 – the President ultimately changed his mind accordingly and gave more resources for naval construction.

King already wanted to increase Essex class production numbers (to 8/year from FY44), plus wanted to incorporate at least four of the big, 45.000 ton armored flight deck carriers proposed by BuAer (later this became the CVB-41 Midway class). At the same time King wanted to keep the capital ship program intact as much as possible (March 1942), while agreeing to convert some of the Cleveland class light cruisers to light carriers, to satisfy the President (who’s personal pet project was the CVL program).

However it was all too clear that this was way beyond existing capacity even for the United States and something had to give. After some discussion (April 1942) and shipbuilding plans drawn up together with BuShips they found out that cancelling some of the BBs and CBs would free up resources to get at least 8 Essex/year. The General Board agreed to have more carriers but did not want to defer BB cunstruction (and also was against the conversion of the CLs, too). The Vice-CNO, Adm. Frederick Horne disagreed with the Board and suggested to King on 4th May to suspend the Montanas.

History interfered at this point as the Battle of the Coral Sea happened to be fought just three days later where for the first time carriers succesfully fought carriers without a single gun shot being exchanged between surface ships. The US carriers turned back the attacking Japanese forces successfully but lost the USS Lexington, one of the precious few big deck carriers the US Navy had in the Pacific.

This probably settled the question as on May 8 King recommened to Secretary Knox to stop the construction of the Montanas in favor of 3 Essex class carriers and 4 Baltimore class heavy cruisers – the order went out to the constructing yards on May 20: Immedaitely suspend all work on the ships!

Knox, probably based on current estimates of completion, ordered the four yet-to be laid down units of the six Alaska class large cruiser suspended as well (that personally hurt King). The order also degraded priority on all other battleships under construction, including BB-60 USS Alabama which was still in early stages of fitting out at Norfolk Navy Yard. The first pair of Iowas dropped to 10th place on the priority list (below the two surviving Alaskas) while the remaining four, BB-63-66 were assigned such low priority that they were practically suspended, too. In the end the more advanced Missouri and Wisconsin had work still going on at a lesser pace (most if not all the long lead time items were complete for them anyway). On the other hand the just recently laid BB-66 Kentucky was stopped and the mid section of the double bottom made watertight and launched to clear the ways for other construction. BB-65 Illinois was not even laid down.

The General Board’s capital ship program was effectively cut in half and the heart of the Two-Ocean Navy act of Aug 1940, the Montana class, ripped out..

As can be seen from the letter excerpt at the head of this part, the General Board tried once, in June to desperately argue for the reinstatment of the class into the building program with the revised charactereistics discussed above. They got rejected. Many put this fact as an indicator of how the General Board’s power declined in shaping Navy policy.

In fact, except for probably the Kentucky, not much actual work was lost. The 116 Mark 7 16″ guns ordered for the Two Ocean Navy Act BB-65-71 battleships were cancelled or suspended, while the heavy armor and main machinery parts already manufactured (mostly only for BB-65 and BB-66) were stored or redistributed to other ships/programs.

Early June saw the Battle of Midway further showcase the aircraft carrier’s power (and it’s extreme vulnerability). In paralel a conversion “mania” spread through Prelminary Design, as conversion to aircraft carrier plans were drawn up for essentially all gun ships still left on the construction menu: Baltimore, Alaska and even Iowa class hulls.

Midway did show on the other hand that

1. the carrier was in certain periods of operation (ie spotting it’s fueled/armed aircraft on deck) extremely vulnerable, to the point that even single, a relatively small, well placed high-explosive bomb could destroy the whole ship

2. without aduqate fast capital ship support the carrier commander (Spruance) had to keep the distance and retire for the night from enemy surface forces

The second half of 1942 reinstated the battleships’ reputation: both as a carrier escort (North Carolina and South Dakota saving Enterprise from more damage at Eastern Solomon and Santa Cruz respectively) and more importantly in it’s primary role: surface warfare, sea control and area denial when Washington and South Dakota stopped Japanese surfaces forces and sank the battleship Kirishima.

Still there was no change in the building plans despite many new found and older proponents of the type within the Navy. Lengthy building times and still limited resources (in terms of building docks/ways) made sure it remained for the time being.

Answering the vulnerabilty of the carrier vessel type, BuAer and Buships came up with the huge CVB-41 class design, sporting armored flight and hangar decks and even cruiser level vertical armor protection with a strong gun battery (initially 9 x 8″ guns later reduced to 18 x 5″). King was enthusiastic for the big carrier and wanted to include four hulls plus wanted to reinstate the 3rd Alaska class unit, USS Hawaii in the 1943 building program. There was one issue though, the carriers displaced 45.000 tons each, as much as an Iowa class battleship. To include them into the program without new tonnage approved by Congress, Adm. King suggested to the President to finally cancel the 5 Montanas and remaining 3 Alaskas and build the 4 CVB and Hawaii instead. The President agreed and so a letter was sent out on 21st July to all three involved Navy Yards informing them about the cancalletion of the Montana class. This was more of a formality than anything else as after Aug 1942 not even official design work was done on the ships.

Medium Sized or 9 gun designs & further battleship design work

It is perhaps the most defining feature of the Montana class, the 2nd gun turret aft that really was responsible for the class going from hero to zero in a relatively short period of time. If we want to be precise it is Turret #3, the superfiring one.

Very telling during the preliminary design stage that once the extremely large designs were out most of the debate revolved around the question if the added firepower of the 4th turret was worth it’s weight or not. More guns meant a much higher probability of hit earlier in a gun fight and also meant more weight on target in a given time period which directly translated to more firepower, in our case 33% more compared to previous ships. However the price was truly very high for that. First of all since penetration and damage per hit was the same no matter how many guns were brought to bear, the relative threatening power against enemy ships was not linear to the number of guns. (The introduction of radar, which was already on the horizon when the designs were made further diminshed this gap.) Second the high speed (25+ knots) hull forms of modern battleships and the relatively large and long machinery plants suited the three turret layouts much better. An additional turret and it’s barbette aft meant an extreme amount of protected buoyancy was needed in place to support it, completely changing the balance of the whole ship and pushing both center of gravity and center of buoyancy aft. This is very evident from the side profile of the Montana class compared to the Iowas. In terms of tonnage a good 6-7ktons was the total cost (see BB65-5 and BB65-11 from the March-July 1940 prelims in Part 2.).

No wonder that quite a few preferred a nine gun option and it was a recurring theme until the suspension of the class in April 1942.

Admiral King, then member of the General Board pushed to have one very late design option added: BB65-13 which was essentially a BB-61 class ship with the heavy secondary battery of 5″/54 guns and the full suit of armor added to enable the 18-32.000 yard immune zone. Even dimensions were the same or very close to what BB-61 had, so this design was Panama compatible. Speed on the other hand dropped to an estimated 28 knots.

Furthermore in January 1942 the General Board asked for 3 more designs that would be focused on revising the secondary and AA armament and it’s layout while reducing overal ship size a bit. It relaxed speed requirements to 27 knots but interestingly allowed for a longer, wider midship part so to enable all secondary and AA mounts being put on more than two deck levels.

A – required 12 – 16″ guns and full protection (18-32kyards IZ) with

a. 16 – 5″/54 guns, 8 twin 40mm Boforses and 24 – 20mm Oerlikons

b. 12 – 5″/54 guns, 8 twin 40mm Boforses and 24 – 20mm Oerlikons

c. 0 -5″/54 guns, 16 twin 40mm Boforses and 24(+) – 20mm Oerlikons

B – same as A above but only 9 – 16″ guns

C – same as A above but only 9 – 16″ guns and somewhat better speed (hinting at BB65-13)

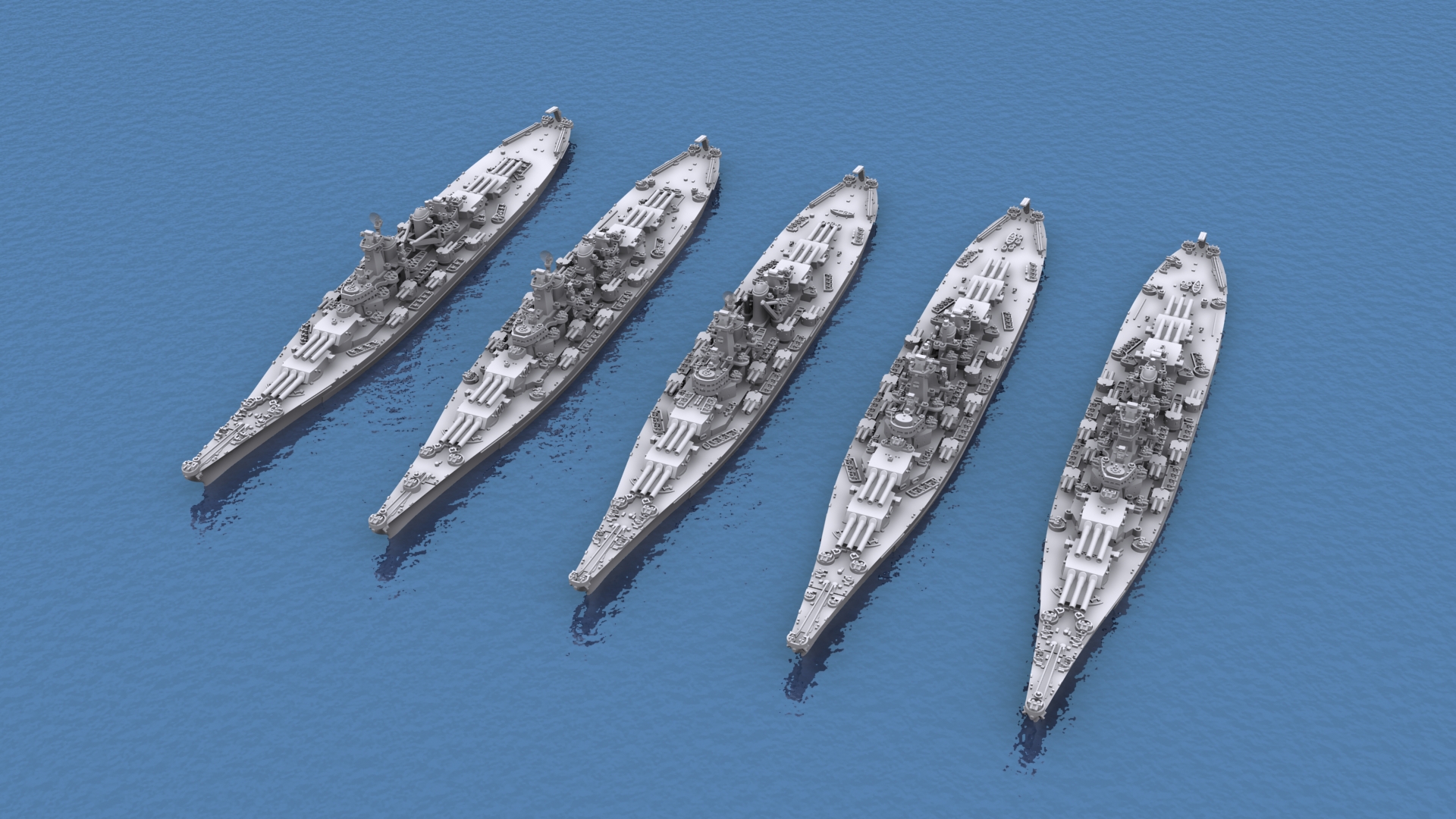

It is interesting to note that 2 out of 3 versions asked for 9 main guns instead of 12 and that the value of the 5″ gun was fairly low at this point. Very minimal trace of any design work responding to this request or any other further battleship studies were found, but a recently surfaced single sheet of paper that compares all fast battleship classes (BB-55, 57, 61, 67) has a fifth coloumn added, with an “Intermediate Tonnage” – Study Only header. This lists a 52.500 tons standard displacement, 820 * 118 * 35 foot design, which is capable of 28 knots, has full protection (18-32kyard IZ) and 9 – 16″ guns with 20 – 5″/54 secondaries and 8 quad 40mm Boforses plus 12 – 20mm Oerlikons. Essentially a shorter , wider BB65-11A having a much less full hull form ie. low block coefficient (probably no long, paralel sides). It is not much (hopefully more would be unearthed in the future) yet it indicates clearly that general preference was in this direction.

When the cancellation happened in July 1943 it was all over for the Montanas but not for the battleship in general as far as the US Navy was concerned. The last pair of Iowa class ships were still alive, even if their priority was the lowest of all fighting ship types. Admiral King however in a directive to BuShips sent in April 1943 emphasized that “desired work on these ships to continue at the maximum rate practicable”. He wanted to defend against possible attrition of the type and to keep the capital ship program alive to some extent, not to lose a capability that was deemed critical and highly needed by the Navy. The letter was passed onto the two involved yards. Philadelphiea wanted to use Slipway No. 3 to lay down BB-65 Illinois in December, 1943. However delays in the launch of BB-64 Wisconsin postponed this to January 1944. Estimated launch was late December 1945 with a completion of July 1946.

Norfolk Navy Yard was in a somewhat better situation as the No. 8 dry dock, intended for the construction of BB-71 Louisiana happened to be free, the double bottom torso of BB-66 Kentucky could be transferred there from storage and restarted in June 1944. Intended launch was November 1945 with a completion of August 1946.

By this time (July 1943) there was an almost unilateral agreement within the Navy that the battleship type was still necessary and required but that the ideal ship would be somewhat better protected (even at the cost of some speed) and have somewhat even better AA gun layout compared to an Iowa featuring similar size but less akward hull form forward. Enter here the “Intermediate Tonnage” study described above.

Since no new ship was expected to be ordered the remaining pair of Iowas were the subject of some redesign to bring them in line with operational realities and to address some defects in detail design. It was known from 1939 caisson tests that the torpedo defense system of the BB-57 South Dakota class had a weak point. The belt armor continued down to the bottom of the ship and as such it was part o the TDS, it being the 3rd bulkhead. Despite it’s taper to 1.75″ at the bottom the armor plate was too rigid to absorb a detonation through proper deformation. It tended to rip from it’s support connecting it to the tripple bottom. Since the BB-61 class used the exact same design and layout the issue was present there, too. While the issue was discovered only in 1939 it was too late to modify the design for the 4 units actually laid down. However the suspension of building provided enough time for Illinois‘ and Kentucky‘s detail designs to be modified so the tapering main armored belt’s attachment points and entry into the triple bottom was changed to reduce the possibility of ripping.

In 1944 BuShips during a cruiser design reviewed the Iowas characteristics. To remedy some errors they suggested to reduce lenght by 40 feet and add a beam or blister of 6′ on both sides covering the ship’s length between the main armored transverse bulkheads. This would have undoubtledly improve torpedo protection but definitely reduce maximum speed to 30-31 knots. They also suggested features taken from the Montanas, like much more subdivided machinery and the elminiation of the aft lower armored belt and it’s armored deck in favor of armored tubes containing the steering leads.

Shortly after the war Adm. Nimitz appointed a comittee to advise on caharacteristics of future ship and aircraft types based on battle experience. Again the battleship was viewed as an important type and senior personnel operating the Iowas deemed the class as an ideal prototype with some sore points to be changed:

- reduce crampedness due to exorbitant manning needs by changing to a smaller number of more effective small caliber AA guns and eliminating single mounts

- eliminate the conning tower and change the superstructure to reduce topweight and clear sky arcs

- put the light AA battery higher up to enjoy the freed arcs

- rearrange the secondary battery to improve end-on fire

- ease station keeping issues for destroyers when refueling (the Iowas were disliked due to their narrow and long stems that made for a special bow wave charactersitic that made at sea refueling them and from very difficult).

In general it was a similar redesign to the Baltimore class to Oregon City or Cleveland to Fargo class improvements. There was an un-official sketch made that was reportedly sent to Adm. King for suggestion in order to incorporate the improvements into the then builing last pair of ships.

Common public misconceptions and legacy

Looking a bit further than a simple design history there are a few recurring points of interest (and urban legends) that are worth addressing. These usually stem from the fact that these ships were the largest planned battleships of the US Navy yet they were more like an alternative than a successor to the Iowa class ships which are of course much better known due to their historical significance, long careers and current museum ship statuses.

- Is it an improved Iowa, or an Iowa with one more turret!?

Probably the most often used statement and question. And the answer is definitely NO. While the main battery guns and their turrets are indeed the same and it has one more turret, the two type shares relatively little else other than that. The Iowa is a fast type where everything was tailored to achieve 33 knots maximum speed whereas the Montanas were conceptualized to maximize firepower and protection over speed (28knots). In fact the Montanas share more design features with the North Carolina class than with the Iowas. One very important difference often overlooked is the beam (108′ vs 121′) which might not be apparent from side views where the two classes profile might appear similar. Iowa was still limited by the 110′ locks of the then existing Panama Canal, therefore the ship’s volume was increased in the vertical dimension. It is very evident in bow on views of the ship or in top down views by the area covered by the 01 deck level, it basically extends out to the side of the hull. The Montana had no such restrictions and it’s volume increases in the beam direction, much lowering the bulkiness and volume of deckhouses above the main deck.

The second and probably more important difference lay in the defensive capabilities of the Montanas which are of course “invisible” traits to the casual observer. Their subdivison and torpedo protection improved resistance to flooding four-fold over Iowa! Essentially progressive flooding would have sunk the ships before all main machinery items could be crippled in a Montana , a feat not many battleship (if any) shared. Furthering that, direct armor protection was also on a different level, Montana having more than twice the immunity zone (the range band where a certain shell could not reliably penetrate the main armor) compared to Iowa and also had more roboust protection against diving shells as well (shells penetrating after some travel in the water).

- It was outdated as it was slow!

Usually speed is the second most critiqued point of the design by the posterity as it is getting compared directly to the Iowas that are predating them. It is important to point out again that the design was intended as the mainstay of the battle fighting line of ships therefore speed took 2nd importance and it only had to match the previous North Carolina and South Dakota classes’. On the other hand the Iowa class which is often praised due to their high speed and tactical mobility was originally intended to oppose the similarly fast Kongo class battleships and also to operate with carriers in task forces or rather for carriers to operate with them in the original, pre-war task force concept. As the war progressed of course the importance of operation with the fast carriers grew but the other task did not cease to exist until late in the war. That being said here is an excerpt from fast battleship operational reports. It clearly shows that very high top speed was nice but far from being necessary to operate together with the carriers unless the ship had to do direct escort even during flight ops or when the carrier was rejoining the task force after conducting flight ops into the wind that was in a different direction. All in all high cruising speed (25knots+) was more important than very high top speed. The latter enabled the faster ship to dictate range in a gunnery fight however the slower ship in our example had more firepower and a lot more armor to take on the faster opponent at whatever range it dictated.

- During the 147 days between and including 6 June 1944 to 30 October 1944, battleships operating with the Striking Force were underway during all or part of 123 days. On 105 of these days boiler power for speeds in excess of 23 knots was required during all or part of the day.

- Ships of the North Carolina and South Dakota classes can make 23 knots with half boiler power (one boiler in each engine room cut in). When boiler power for speeds in excess of 23 knots is required, it is necessary to cut in all boilers, in order to operate each engine as a unit, with no cross-connections open. While it is possible to make over 25 knots with one boiler secured, by running the shafts at different speeds, this is not standard practice and is resorted to only when necessary to secure one boiler for a short period, as for example to renew a leaking gasket.

- This high percentage of time operating under full power conditions results in greatly increased upkeep requirements. The life of boiler brickwork and tubes is shortened and the reliability of the main propulsion plants is seriously compromised.

- It is recommended that battleships of the North Carolina and South Dakota classes be not required to cut in boilers for speeds in excess of 23 knots unless there is some prospect that the battleships themselves will be required to make such speeds.

- It would appear that the great majority of carrier task group operations can be accomplished without requiring the supporting battleships to increase speed above 23 knots. If the task group steams into the wind for 30 minutes with the carriers making 27 knots and the battleships making 23 knots, the resulting separation will be of the order of 4000 yards. It is believed that this separation can be accepted under all but the most immediate prospects of enemy attack.

- An Iowa could do almost the same why build the bigger, more expensive one?

While certainly true that as history panned out many if not all tasks could be handled by the Iowa class just as well as the Montanas could have (bar going toe to toe with a Yamato class unit). It must not be forgotten though that none of the US Navy fast battleship classes were subject to near-peer adversary gun fights so we do not know for sure what punishment they could stand up to. In that regard Montana was most certainly in a different league compared to all three historical classes. Finally when their design was put to paper no one could have known for sure if any new, much more powerful enemy battleship type would be out there to oppose them (in fact Preliminary Design at some point preferred 18 inch guns as rumors about the Japanese Yamato class ships trickled in). That is exactly why the Montana class was needed: an insurance ticket against all odds. And basically everyone from the President down to the various Navy Bureaus acknowledged that one way or the other.

Recap, Bridge layouts, personal critics

Normally I do not write lengthy addendums to Genesis type articles but since this one was really the ‘raison d’étre’ for the whole blog and is a personal favourite of mine I thought I would add some further points for the real hardcore enthusiasts of the topic out there.

First of all this series is based on by far the deepest research I have done so far and I’ve also tracked down as many primary and secondary sources as I could get my hands on and this involved related aspects, too (like navy yard and ship building capacity data etc.)

Yet as is usual in such situations the more one learns opens up even more questions to be answered but I thought I’ll draw the line here and publish the 3rd part with what is known by December 2024.

Hopefully in the near future more info will appear from NARA and other sources to cover for at least some of the open questions – so a potential Part 4. might be possible sometime.

What these open questions are?

While the BB-55 class genesis is nicely covered with great detail it is much less true for the following classes. BB-57 and 61 design periods are relatively straighforward though as the main design goals were clear early on so relatively little remains on the table. Not so with BB-65. It is highly convoluted and even the basic settings were mashed up twice during the design period. Therefore some ‘dead ends’ are only very vaguely covered and these would probably greatly add to the overall story. For example what about the other April 1938 designs with 18″ guns (if any)? What about the fast designs , especially the BB65-Y1-3 variants or the BB65-8A-D ones and their msysterious special machineries (6 prop shafts anyone)? Fragments from each are available but show only how much more is hidden there.

The second group of questions are related to certain detail elements of the final design, most notably the tank towing test model hulls, the bridge layout and the secondary battery turret’s shape and form. There is a better chance we will get answers on these sooner though.

The bridge layout question came up when detailed weight breakdown data became available for both Division and Force flagship variants. The difference indicates or at least hints at the possibility of a heavier conning tower in the Force flagship configuration, which would be fairly logical given the same was done in both South Dakota and Iowa. As mentioned many times though the Montanas reflected much more on the original fast BB class, the North Carolinas then the preceeding two classes. This was true for the bridge layout as well. General preference was for a separate pilot house and conning tower setup which NC is a perfect example of. This allowed for much less restricted view from the pilot house and also allowed to seat the conning tower in the lowest possible position, where it’s lower level’s vision slits would just about clear the top of Turret #2.

This solution obviously had one major drawback as well, namely that the top of said turret had to be left clear of any equipment, let alone AA guns in order not to block the view in a battle situation where the commanding officer would quite probably be in the CT’s lower level (the upper level was housing fire control functions).

The South Dakota arrangement (which was almost carbon copied on Iowa) the function of the pilot house and the conning tower were partly combined due to extreme lack of space (again these designs had to grow in the vertical dimension). The conning tower itself was raised more than one level compared to NC with the base being almost at the same level as the top of Turret #2. The small pilothouse was tucked behind the CT with a small corridor left between the two. Later-on all ships in these classes had a gallery platform added around the forward part of the CT, essentially creating a pilot “gallery”. During the war the galleries had roofs added then the whole plated in with rows of windows, giving a signature look. In essence these were extended pilot houses.

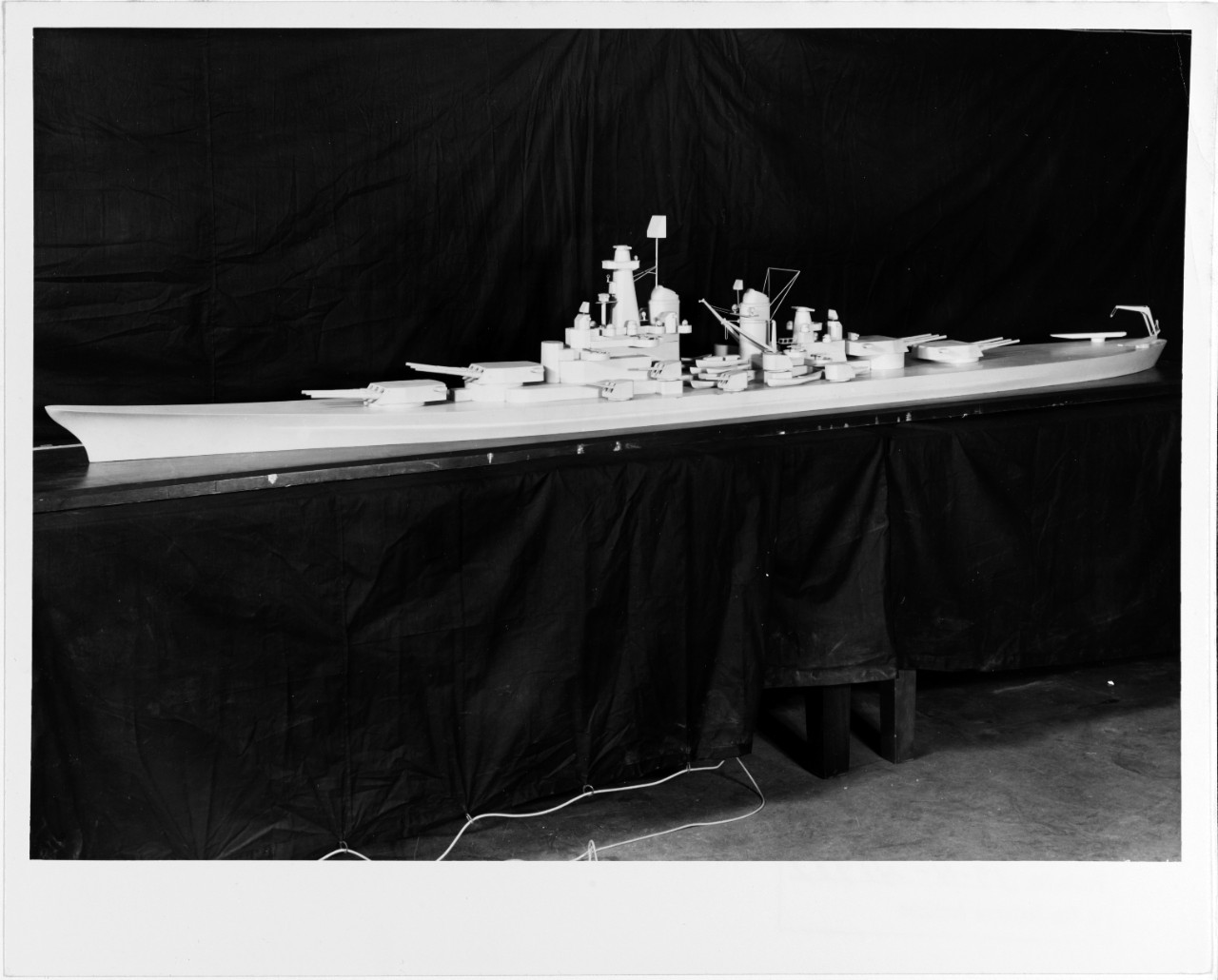

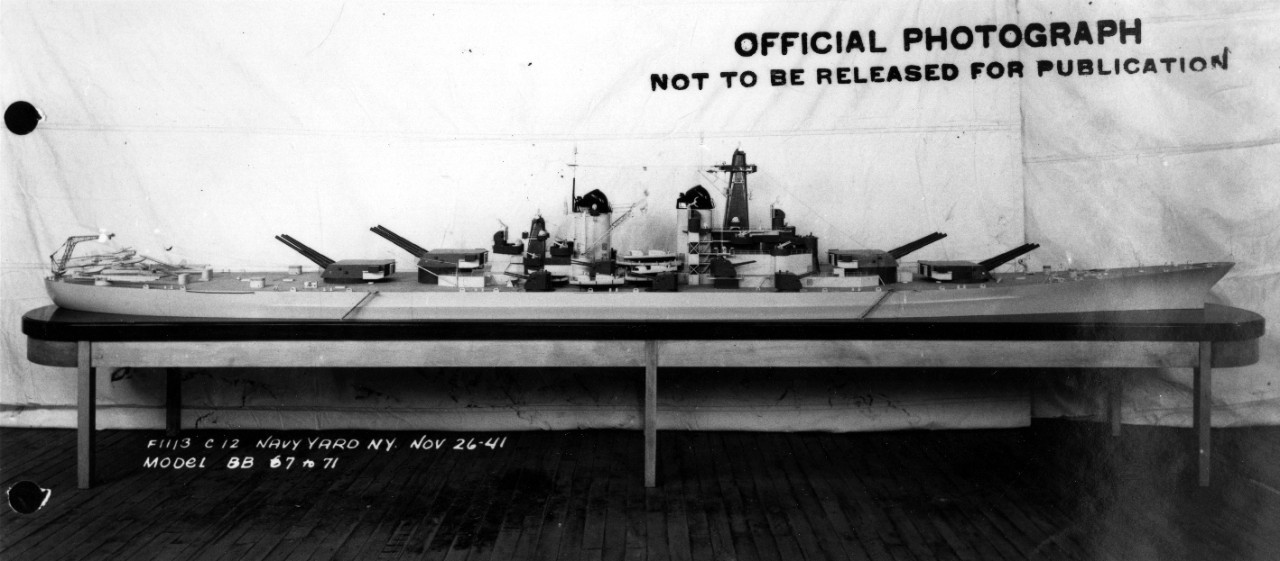

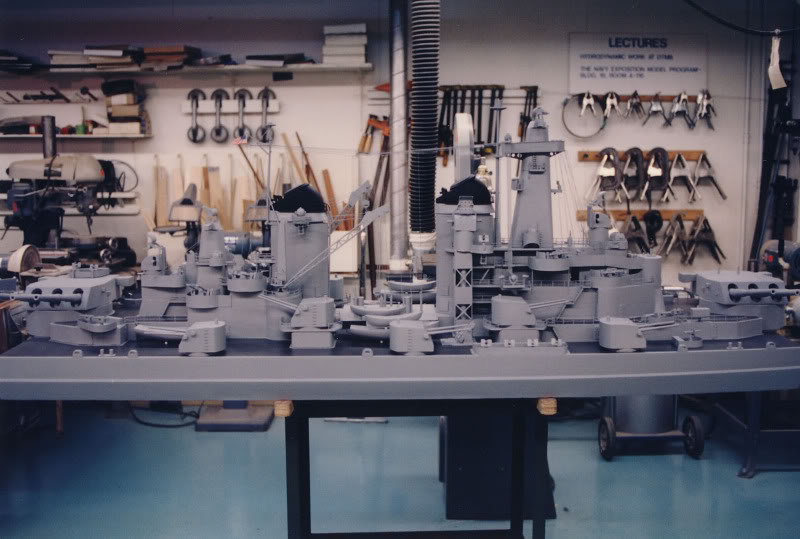

The Montana class Booklet of General Plans is dated from May 1941 so it shows BB-67-4 as conceived. Also the title says BB-67-71 General Arrangement, with no specific ship selected (understandable as hardly any detail design was done). Now this BOGP corresponds to the early official Navy drafting office model, that is fortunately with us even today!

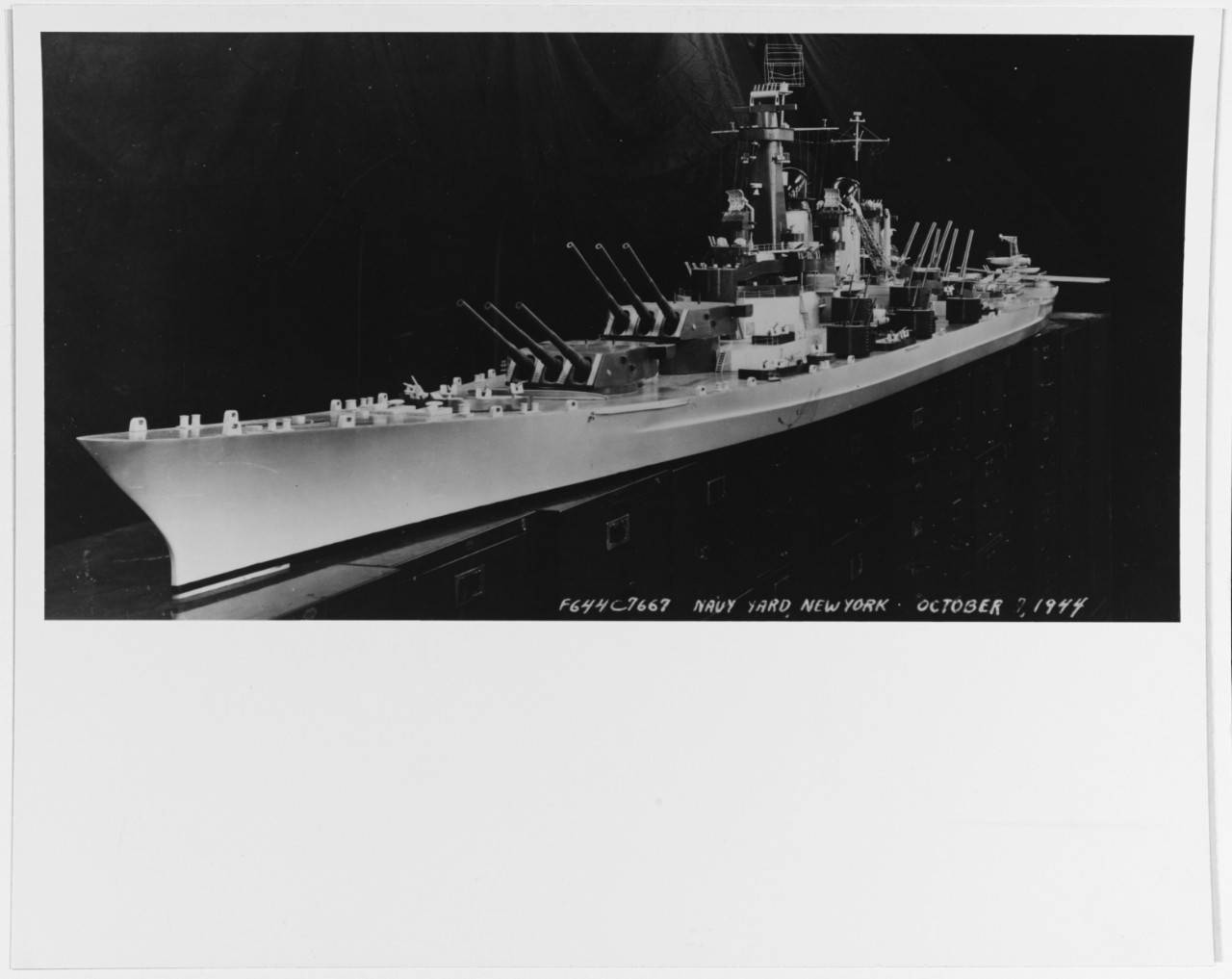

These clearly show a very elegant layout which is very similar to North Carolina, with the pilot house well above the top of the CT but sitting a bit more forward from the fire control tower. This allowed to add two Mk 51 directors just behind and outside the back of the pilot house for the forward pair of quad Boforses. As the design refined a new model was made in November 1941 which changed a lot of small features that were changing on in real life battleships as well at that time. This included the deletion of quite a few armored rangefinder hoods and also changed the contour of the forward superstructure, with better spacing and much better forward firing arcs for the four quad 40mm Bofors mounts sitting there. The two Mk 51 directors were moved to the forward roof of the pilot house from just aft of it, to sit right at the base of Mk 37 secondary battery director’s barbette.

The pilot house was countersunk a bit into the superstructure’s top plating just enough that it’s portholes peek above the top of the conning tower. Later during the war (we do not know when, but presumably during 1942) this second model was refined and rebuilt somewhat, adding mostly light AA (20mm Oerlikon) galleries and the two stern mounted quad Boforses plus updated mast and radar arrangement (with what appears to be an SK main air search set on the foremast and an SG surface search on the mainmast). Fortunately this model is still in existence as well.

And now the 10.000$ question: how does one add a triple level conning tower into this pretty confined and streamlined space especially if one does want to add a quad Bofors on top of Turret #2 too since it is probably the best AA gun location on any battleship. There I think might be three possibilities:

- forget the 3 level conning tower, enlarge to lower level to the sides with it being an oval shaped affair, somewhat similar to what the Tennessee/Colorado classes had – the issue with this is the firing arcs of Turret#2 would suffer on aft bearings and also mixing ship and fleet command and their staff is not exactly convenient

- add the 3 level CT in place of the existing 2 level one and raise both the chart house and the pilot house and the Mark 37 director on top of it just enough that the portholes of the pilothouse would clear the top of the new, taller CT – this would pretty much obstruct sky arcs and make for quite some interference

- use something like what the SoDak/Iowas have ie. add the 3 level CT in place of the existing 2 level one with perhaps raising it to the level of Turret #2’s top and accept that the pilot house would be blocked from view by the top level of the CT – build a gallery platform around the CT and plate it in, creating an “extended” pilot house/gallery

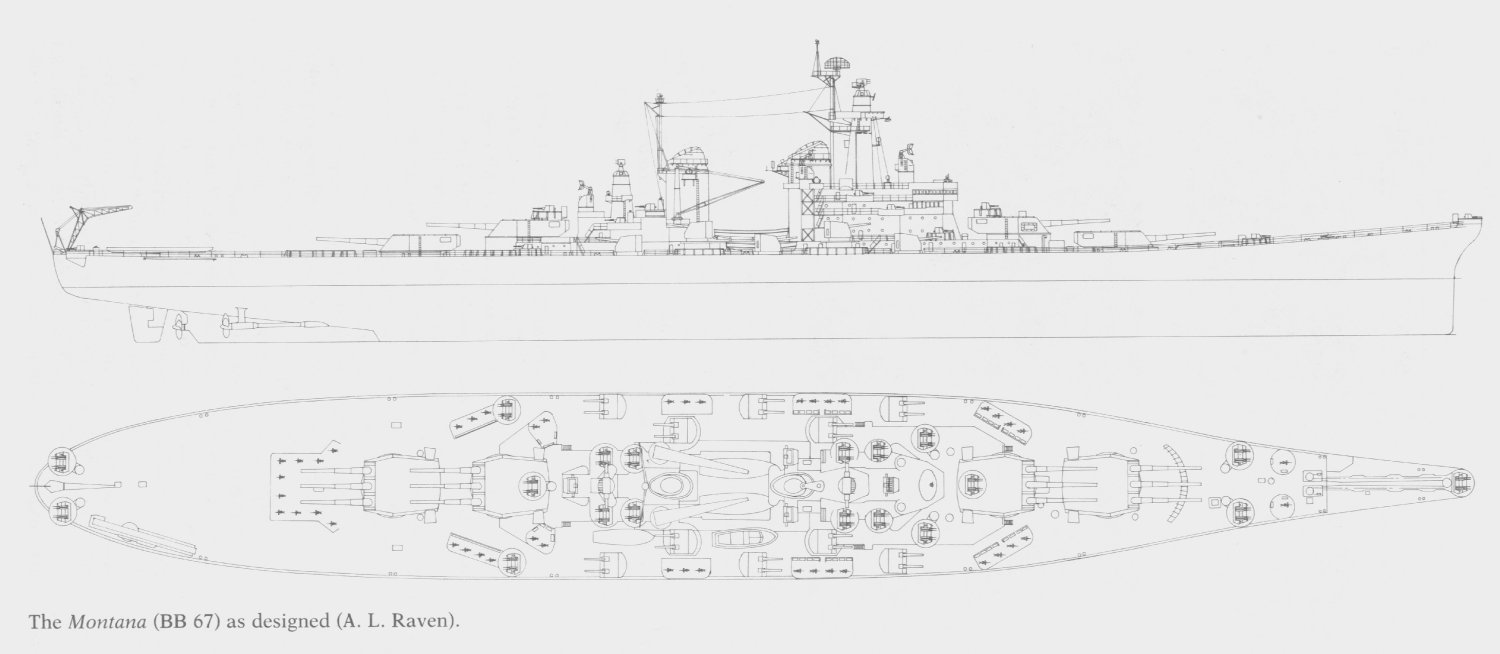

Apparently this was the opinion of Alan Raven too, for his illustration of N. Friedman’s book, showing a concept of the ship as completed.

When creating the renders of each individual ship together with Roe Tengco we ran immediately into the issue of the T#2 Bofors mount not being compatible with the draft model bridge layout. Contrary to North Carolina and Washington, that never had that mount due to the same reason we thought that still, this position is too good to be left out. Many commentators and operational personnel praised such mounts stating that the capacity to provide continous fire at targets crossing the bow literally doubled the effectiveness of AA fire. It’s true that the bow mounts were there but they were sitting much lower and for example could not engage a torpedo bomber from the bow (not to mention the turret top mount was always operable, regardless of sea conditions).

Now the question of the secondary turret’s shape is probably more commonly called into question as the 5″/54 Mk 16 guns were intended to be housed in a supposedly new mount. However no official plans, drawings or photos of mock-ups of the proposed Mk.41 twin-gun mount’s gunhouse are known to exist. Every rendering is just a theoretical enlargemnt, a duplication of the single gun Mk 39. mount used on the Midway class carriers. Also all the official navy models were built with the older, Mk 28 mounts which were perfectly capable to hold the longer guns. The BOGP also indicates the older mount.

On the other hand it is quite probable the new designation was given to differentate these mounts based on secondary, less visible features (just as the Mk 32 mount used on cruisers & carriers or the Mk. 38 used on destroyers). Almost certainly the Mk 41 would have had more powerful electric motors for both turning the turrets and elevating the guns, quite pprobably thicker plating and somewhat different cutouts for gun ports and spent cartridge ports.

This concludes the Montana class Genesis for the time being. Future information might lead to an addition of a 4th Part.

If you liked this article please consider supporting the page and keep it ad free through my Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/c/csatahajos22/shop

Sources:

Norman Friedman: US Battleships, An Illustrated Design History

Norman Friedman: Battleship Design and Development

Dulin & Garzke: US Battleships

Warship Internation (several issues)

+ various internet sources

I would like to express my thanks to the following people who greatly helped my in writing this series:

- William Jurens, who kindly contributed the machinery and steering arrangement drawings

- Chris Wright of Warship International, who kindly answered my endless questions

- Zoltán Takács who kindly drew the preliminary designs in modern format

Budapest – May, 2025